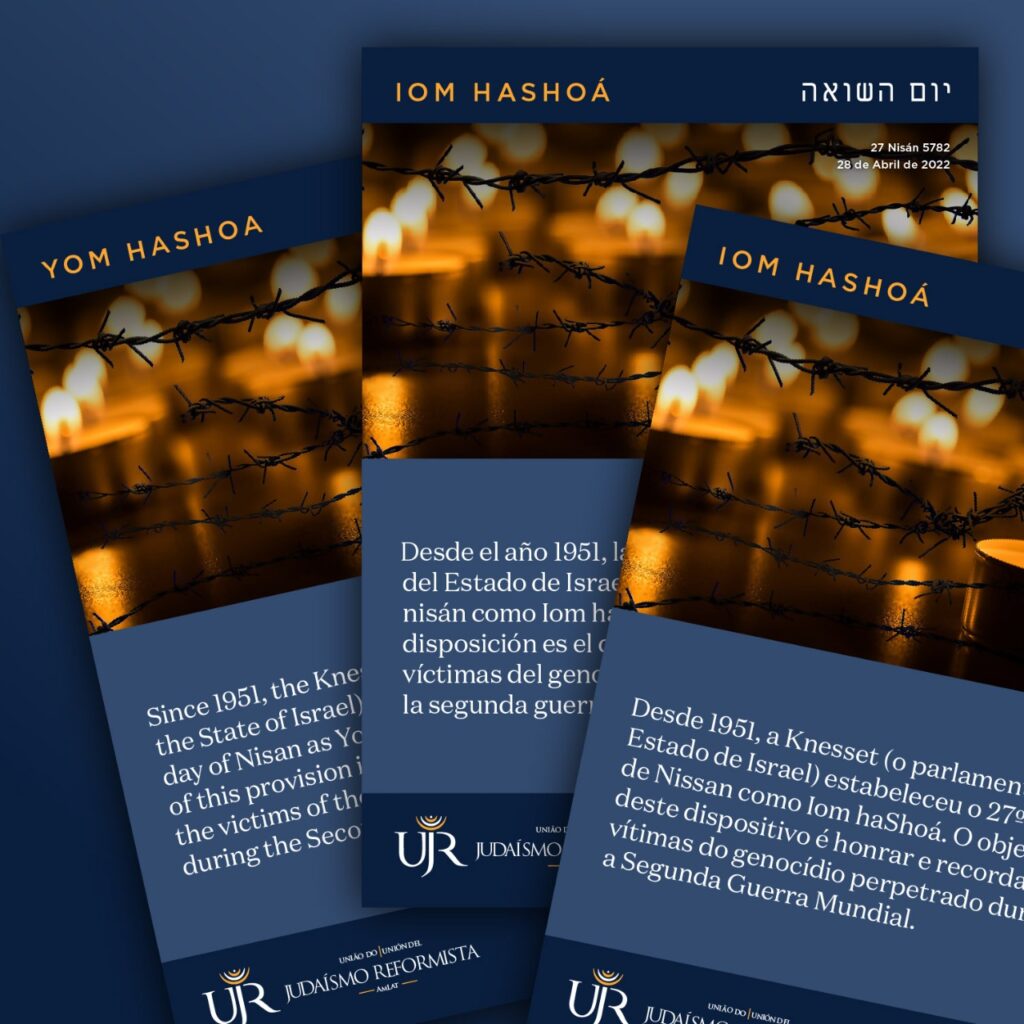

27 Nisan 5782 / 28 April 2022 / Yom haShoah יוֹם הַשּׁוֹאָה

Since 1951, the Knesset (the parliament of the State of Israel) has established the 27th day of Nisan as Yom haShoah. The purpose of this provision is to honor and remember the victims of the genocide perpetrated during the Second World War. The date is close to Yom haAtzmaut, the day of independence of the State of Israel. This often generates a profound sense of contrast between the tragedy of death, and the affirmation of life and national autonomy. In addition to the state origin of this remembrance date, the meaning of the Shoah memory is a central issue for all our communities.

One of the most frequently asked questions in the face of horror is whether God was absent. French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas proposes that those who speak of the absence of God during the Shoah refer to a “primary” god who works according to the logic of punishment and reward. For Levinas, God awakens in us the possibility of filling us “with the highest thoughts”, in order to make us responsible for history and for the life that reveals the face of our neighbor. As well as an “emancipated person who remembers his servitude and is in solidarity with all the subjugated”¹. In the same vein, Martin Buber speaks of an “eclipse of God.” Humanity was too busy superficially bonding with each other or with divinity through any means, but not able to face the human or the absolute in depth. Cut and eclipsed by these dialogues, tragedy ensued².

Building deep bonds of mutual care is a challenge our movement has taken very seriously. We consider it a mitzvah³ to remember those who lost their lives during the Shoah. The rituals that were developed seek to deal with the complexity of remembering millions of people, while evoking a feeling of deep fraternity and closeness⁴. The publication “Six Days of Destruction” is a Reform effort to bring poetry and prayer to the silent memory of six million people. Although it is impossible to remember them all in the magnitude of what they should have lived. Its author, Elie Wiesel, explains: “We can never remember all the days of destruction, just a fragment. Don’t cry, my fellow Jews. Above all, don’t cry. That would be too easy. Let us hear your tears, which flow within us without sound, without the slightest noise. Let’s listen.”⁵

As we have seen, however, spiritual eclipses and lack of responsibility cannot be countered by national laws or mere rituals. The human being has to be shaken. The risk is in our reaction. The memory of horror can generate fear and distrust of the other. Bridges that were broken before the Shoah can never be rebuilt. Ricarda Klein, a Shoah survivor, warned us against this in her accounts and interviews. “Fear anesthetizes us against pain, unrest and discomfort”⁶. Yom haShoah cannot invite us to be afraid, because it does not allow us to feel what is happening around us. “Those of us who survived this holocaust are imbued with new hopes and dreams, but never erasing the past.”⁷ Memory exists, but as a driving force for hope and life. We must feel to overcome the terror that anesthetizes and separates us, we must listen to the silence to awaken the desire to make more voices resound. To live with vision, hope and fraternity.

Hernán Rustein

Rabbinical Student

Libertad Temple – Jewish Foundation

—

Folheto Português Folleto Español Flyer English

- Lévinas Emmanuel, and Manuel Mauer. Difícil Libertad y Otros Ensayos Sobre judaísmo. Lilmod, 2008. (Págs. 206 – 218). Levinas, Emmanuel. Totalidad e Infinito: Ensayo Sobre La Exterioridad. Sígueme, 2006. (Págs. 57 y 210-213)

- Buber, Martin. Eclipse De Dios: Estudios Sobre Las Relaciones Entre religión y filosofía. Sígueme, 2014. (Págs. 117 a 145)

- Uma prática que une judias e judeus com sua tradição, e que eles julgam ser uma boa prática

- Entre outras práticas realizadas nesse dia, muitas vezes são feitos esforços para estudar o que aconteceu principalmente através de testemunhos. Há aqueles que fazem refeições frutíferas, comemorando as experiências das vítimas. Além disso, a tsedaká é frequentemente direcionada a instituições que mantêm viva a memória do Shoá. Por outro lado, foi criada uma liturgia específica, combinando a recitação de poesias modernas com a liturgia tradicional e o acendimento de velas de recordação. Ver as seções “Yom Hashoah” em Knobel, P. (1983). Gates of sesons. Nova York: CCAR Press; Washofsky, M. (2010) Jewish Living: A guide to contemporary reform practice. Nova Iorque: URJ Press e no sidur reformista “Mishkan Hatfilah”.

- Wiesel, E. (1988). The Six Days of Destruction. Oxford, Inglaterra: Pergamon Press. (Pág. 51)

- Klein, R. “Banana Split” não publicado

- Klein, R. (19 de Marzo de 2019). Ganarle a la guerra. Obtenido de https://virgeninmaculada.wordpress.com/2019/03/29/ganarle-a-la-guerra/